Hello, I’m ryoppippi. Nice to meet you if we haven’t met before!

Over the past few years, I’ve created various CLI tools as OSS projects:

In the JS ecosystem, various libraries constantly appear and disappear. I’ve tried many different tools myself, and here’s my current stack for CLI tool development as of 2025.

My Principles

When creating CLI tools as OSS, I keep these principles in mind:

- Choose libraries that guarantee type safety

- The smaller the bundle size, the better

- Provide comprehensive documentation

- Take maximum precautions to prevent malicious code injection

Stack

Package Manager

I use bun for the following reasons:

- Lightning-fast installation: It’s incredibly fast. You can set up environments blazingly fast both locally and in CI

- Native TypeScript support: You can directly execute TypeScript files with

bun run, improving the development experience - Excellent compatibility: Very high compatibility with Node.js - I haven’t encountered any compatibility issues so far

- Useful extensions: bun shell is particularly handy for writing simple scripts or executing shell scripts within

package.json

While pnpm had the edge for monorepo usage, bun is catching up with the recent implementation of pnpm style isolated install. Once this stabilises, bun will become more suitable for monorepos as well.

Bundler

I currently use tsdown, a bundler for JS/TS based on rolldown, which is written in Rust.

Rolldown is a project that aims to reimplement rollup in Rust. While still under development, it’s promising because it aims to achieve rollup’s excellent tree shaking capabilities with Rust’s performance.

Here’s why I chose tsdown:

- Blazing fast builds: Overwhelming speed thanks to being Rust-based

- Superior tree shaking: Inheriting rollup’s design philosophy, it offers more accurate tree shaking than esbuild or bun build

- Integration with quality assurance tools: Excellent integration with tools like publint and unplugin-unused

- Rollup plugin compatibility: Being able to use unplugin plugins directly is a huge advantage

- Simple configuration: Very simple config files, including type generation and source map generation

- Continuous improvements: Benefits from rolldown updates, such as bundle size reduction

When comparing bundle size and build times, I’ve achieved better results than unbuild, mkdist, tsup, and bun build.

Particularly, esbuild-based tools tend to have less accurate tree shaking, resulting in larger bundle sizes.

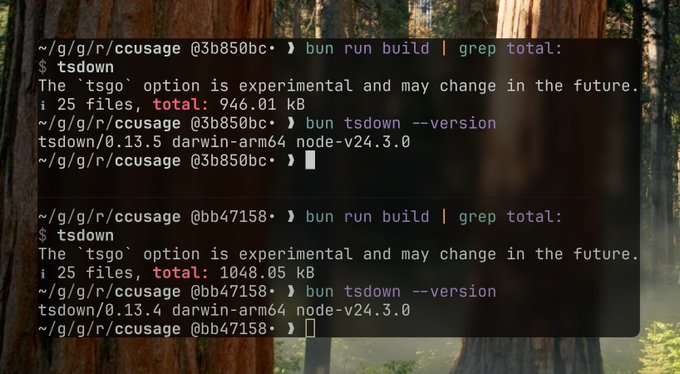

Here’s an actual example of bundle size improvement through tsdown and rolldown updates:

I just update tsdown from 0.13.4 -> 0.13.5 - same codebase - same dependencies - same tsdown configuration but the total bundle is -100KB what happend!??! @sanxiaozhizi @boshen_c @TheAlexLichter

Before rolldown came along, I was a devoted bun build user and even created plugins for bun, but I switched to tsdown as it proved more convenient.

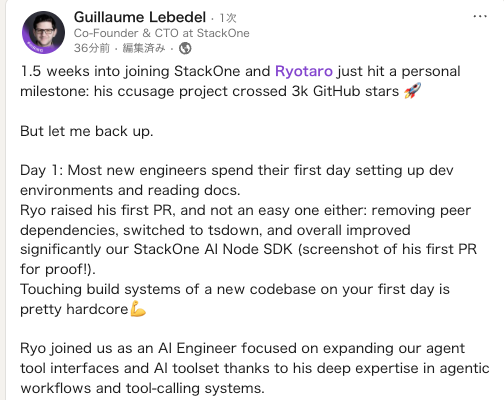

It’s been incredibly useful at my new job too!

入社してすぐですが、すでにCTOにバチクソ褒められているので英語が読める方は見ていってください linkedin.com/posts/guillaum…

I used to frequently use

tsup, but since the author has also switched totsdown, I’ll likely be usingtsdownmore often going forward.Replying to @hiitsricardo tsdown is the future, the author @sanxiaozhizi is also a contributor to tsup, but it's indeed no longer actively maintained

Bundling Strategy

When distributing CLI tools, I bundle all dependencies and keep dependencies at zero. There are clear reasons for this:

- Faster installation: Dependency resolution is slow. While

bunis fast, it’s noticeably slower withnpmordeno - Efficient code distribution: Tree-shaking ensures only actually used code is included. Distributing as dependencies would mean downloading unnecessary code

- Operational stability: Avoids issues from version mismatches. CLI tool users don’t need to worry about dependency versions, so including all packages at a specific point ensures consistent operation

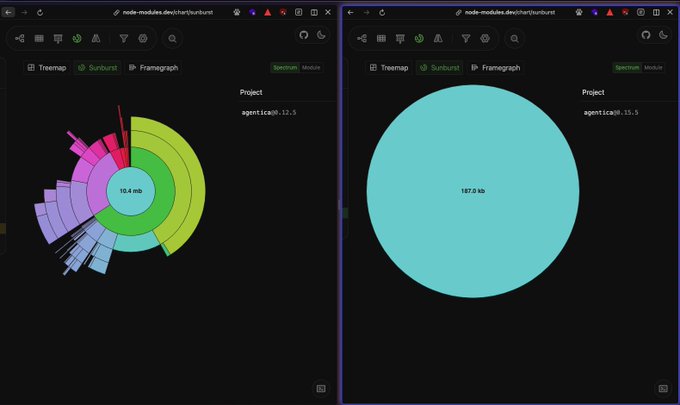

This strategy significantly reduces distribution size:

仕事としてのOSS、バンドルサイズ編 👈before(インストールサイズ10.4MB+6個の依存) after👉 (インストールサイズ187KB + 0個の依存)

To keep bundle sizes small, I prioritise the following when selecting libraries:

- Small size with minimal dependencies

- Effective tree shaking compatibility

- Provides necessary features without excess

For example, ccusage stays under 1MB even without minification:

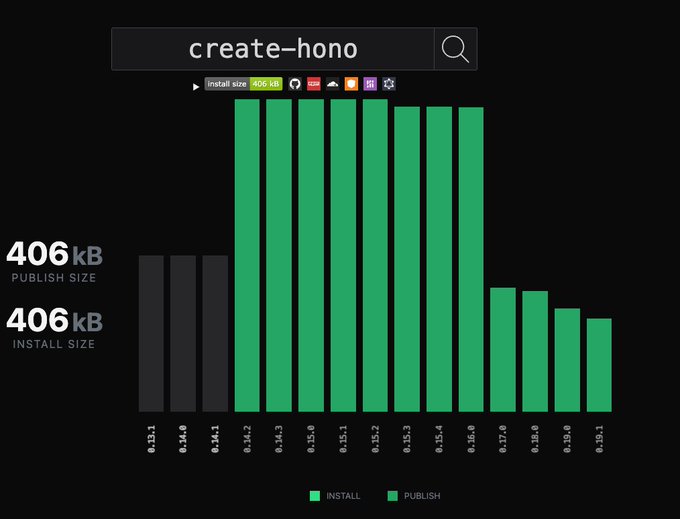

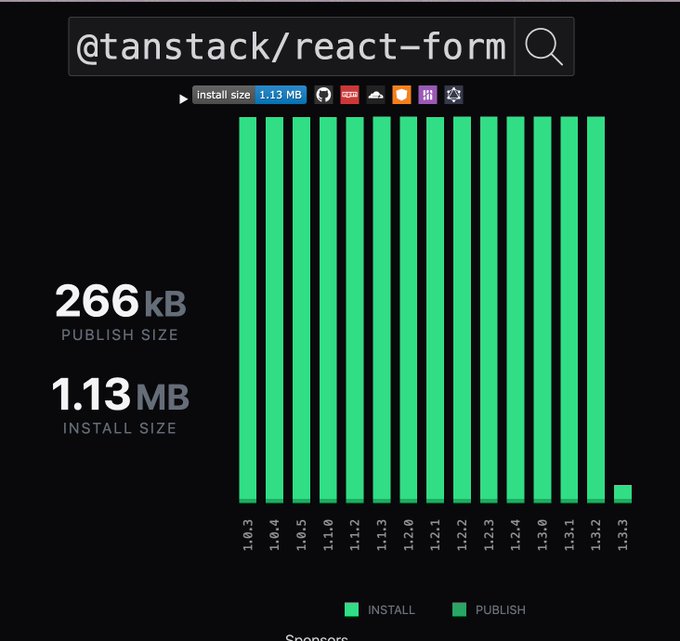

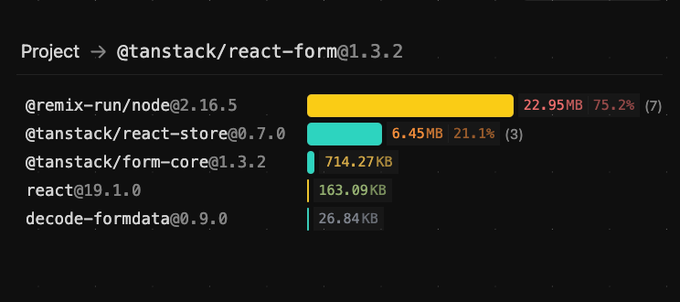

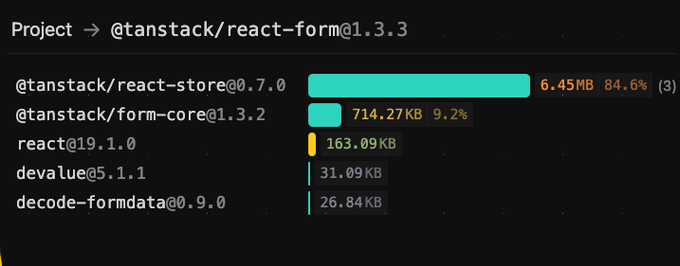

I also contribute to frequently used tools to reduce their bundle sizes:

create-hono(@honojs) package size

packagephobia.com/result?p=@tans… packagephobia works finally. This is a great visualization

x.com/ryoppippi/stat… こちら、マージされました pnpmではインストールサイズが30MB->7.62MBになっています (react-domがそのうちの6.33MBを占めているのでこれ以上は厳しいと思われる)

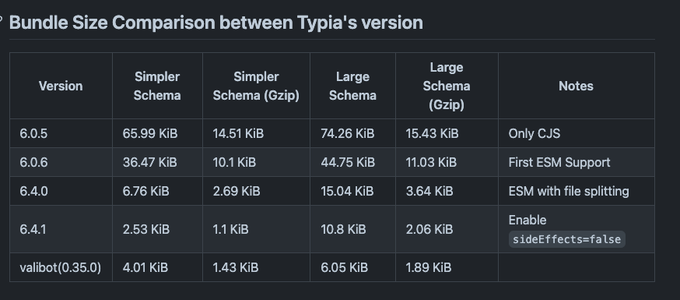

TypiaのESM化、Bundle Sizeの最適化を進めていったところ、ここまで小さくなった! ここに来るまで1ヶ月くらい 実装自体はあんまりいじってないので、v7になるともっと小さくなるかも github.com/ryoppippi/thes…

CLI Framework

I’ve tried various JS frameworks:

Currently, I mainly use KAZUPON’s gunshi:

- Type-safe API:

parseArgs-like API with type-safe command-line argument parsing - Comprehensive features: Includes negatable, enum, alias, type checking, and more

- Small bundle size: Lightweight compared to other frameworks

- Active development: Innovative features like plugin systems are being added

- Future potential: Shell completion, i18n, and help customisation are in development

I originally used cleye, but migrated to gunshi as it maintains a similar interface while being lighter and more feature-rich.

Example of using gunshi in curxy

https://github.com/ryoppippi/curxy/blob/7073bf01ce6c5b87f068d36bf3d9bb247af8f998/main.ts#L15C1-L90C4

const command = define({

toKebab: true,

args: {

endpoint: {

type: 'custom',

alias: 'e', // alias configuration

default: 'http://localhost:11434',

description: 'The endpoint to Ollama server.',

parse: validateURL, // custom validation function can be set

},

openaiEndpoint: {

type: 'custom',

alias: 'o',

default: 'https://api.openai.com',

description: 'The endpoint to OpenAI server.',

parse: validateURL,

},

port: {

type: 'number',

alias: 'p',

default: await getRandomPort(),

description: 'The port to run the server on. Default is random',

},

hostname: {

type: 'string',

default: '127.0.0.1',

description: 'The hostname to run the server on.',

},

cloudflared: {

type: 'boolean',

alias: 'c',

default: true,

negatable: true, // automatically generates `--no-cloudflared` from `--cloudflared` option (https://gunshi.dev/guide/essentials/declarative-configuration#negatable-boolean-options)

description: 'Use cloudflared to tunnel the server',

},

},

examples: ['curxy'].join('\n'),

// Type-safe argument type definitions

async run(ctx) {

const app = createApp({

openAIEndpoint: ctx.values.openaiEndpoint,

ollamaEndpoint: ctx.values.endpoint,

OPENAI_API_KEY,

});

await Promise.all([

Bun.serve(

{ port: ctx.values.port, hostname: ctx.values.hostname },

app.fetch,

),

ctx.values.cloudflared

&& startTunnel({ port: ctx.values.port, hostname: ctx.values.hostname })

.then(async tunnel => ensure(await tunnel?.getURL(), is.String))

.then(url =>

console.log(

`Server running at: ${bold(terminalLink(url, url))}\n`,

green(

`enter ${bold(terminalLink(`${url}/v1`, `${url}/v1`))} into ${

italic(`Override OpenAl Base URL`)

} section in cursor settings`,

),

)

),

]);

},

});

Logging

I use consola for log output. It’s attractive for its ability to easily produce rich logs:

- Rich log levels like success, info, error

- Rich output features like boxes and tables

- Simple user input collection using prompts

While not the smallest in terms of bundle size, I chose it for its balance of features.

For more interactive interfaces, I sometimes use @clack/prompts.

Testing

I use Vitest for testing CLI tools. Vitest offers several advantages for CLI tool development:

- High performance: Extremely fast execution thanks to its native ES modules support

- Safe environment variable mocking: Provides safe and isolated environment variable mocking, crucial for CLI tools that depend on environment configurations

- In-source testing: Allows writing tests directly alongside source code using

if (import.meta.vitest), eliminating the need to export functions purely for testing purposes

In-source testing is particularly valuable for CLI tools because it allows testing internal functions without cluttering the public API. You can keep implementation details private while ensuring comprehensive test coverage.

Distribution

npm

I upload packages to npm for distribution.

I previously had high hopes for JSR-IO. JSR had attractive features like publishing TypeScript directly without building and automatic documentation generation. However, for CLI tool distribution, it had these issues:

- The only practical option to run tools on jsr is using deno

- CLI tool users don’t necessarily use deno

- When you can control your own build process and documentation generation, JSR’s advantages diminish

Therefore, I returned to npm for its versatility.

Security

Security concerns are often raised about npx execution. To address this, I use OIDC authentication and CI/CD through GitHub Actions to demonstrate package safety. This allows users to verify that distributed packages are trustworthy.

Recommending bunx

本日のなるほどスレすぎた…。ツール配布用にbunxを選定したくなる理由、説明してもらったら納得感がかなりありました

ccusageは依存パッケージが0なのでおそらく速度は変わらないんですが、依存が多い系が遅いんですよね。ダウンロードとpackage resolutionで速度差がある印象 bunx @modelcontextprotocol/inspector deno -A npm:@modelcontextprotocol/inspector で比較してます(なぜかdeno版は起動失敗してますが)

bunx is bun’s package execution tool, essentially bun’s version of npx. It provides functionality to temporarily download and execute packages from the npm registry with these characteristics:

For my OSS projects, I recommend using bunx when running CLI tools from npm. I generally don’t recommend global installation like npm i -g <package> for my packages.

Here’s why:

- Fast installation: Uses

bun install, making it significantly faster thandeno npm:fooornpx -y foo, especially noticeable with tools that have many dependencies - Maintained compatibility: Executes with node if node is specified in the shebang, maintaining runtime compatibility while benefiting from faster installation

- Clean environment: Creates cache in

/private/tmp, avoiding user environment pollution - Automatic updates: Cache automatically revalidates every 24 hours, ensuring you always use the latest version (clear advantage over global install)

For packages with appropriate bundle sizes where frequent version pinning isn’t necessary, CLI execution via bunx foo balances user convenience and reduces maintenance burden. I believe bunx execution is optimal, especially for frequently updated CLI tools like ccusage.

Recently,

ccusagewas added tohomebrewwithout my knowledge, but since it’s not my recommended method, I haven’t added it to the documentation.

Documentation

I primarily use Claude Code to enrich READMEs. For larger projects, I sometimes create documentation using vitepress.

Vitepress isn’t just a static site generator; it excels in:

- Integration with

typedoc - Ability to add features like

llms.txtgeneration as plugins - Beautiful code highlighting using

shiki

Other Tools

- bumpp: Tool for easy semantic versioning

- publint: Tool for maintaining package quality

- clean-pkg-json: Removes unnecessary package.json fields before publishing

- changelogithub: Creates beautiful GitHub Releases

- renovate: Automates dependency updates. Highly configurable with auto-merge capabilities

- eslint: Tool for maintaining code quality. I use biome with fewer contributors, but with more contributors, rules make reviews easier. Rules are managed with @ryoppippi/eslint-config. Looking forward to oxlint’s type-aware rule development

- pkg-pr-new: Automatically publishes packages to npm-compatible registry per commit. Easy to test locally

- bun-only: Used when creating tools that only work with

bun

Conclusion

I’ve introduced my stack for CLI tool development as of 2025. Looking back, I’m reminded of how much I rely on various libraries and ecosystems to advance my development.

I look forward to new libraries and tools making CLI tool development even more convenient in the future.

Addendum

If you’re interested in the internals of ccusage, check out deepwiki.